In defense of the WTF?! parts of the Bible (and our lives)

And other tips for driving a tent stake through some Canaanite's skull

Welcome to another installment of the “In Defense of…” series—where I’m reflecting on some of the more challenging (to me) parts of the Bible as I read through it over the course of 2025. Check out this page for a current list of all posts as well as other information and resources about this project.

“But when Sisera fell asleep from exhaustion, Jael quietly crept up to him with a hammer and tent peg in her hand. Then she drove the tent peg through his temple and into the ground, and so he died.”

(Judges 4:21, NLT Chronological Bible reading for April 1)

In my teenage years, the youth pastor at a large evangelical church I attended insisted every Bible passage had a practical application. First read a Bible passage to understand it literally, he would say, then to find a takeaway for your life. I wonder what he’d say about the story of Jael.

A member of the Kenite tribe—a nomadic people that traveled in friendly proximity to Israel—Jael lived at a decisive time in biblical history. Although the Israelites had lived in the Promised Land for some 300 years already, they hadn’t fully conquered it yet. Instead, they were stuck in an exhausting cycle of forgetting God, being conquered, repenting, then being rescued by a divinely appointed judge (part prophet, part legal mediator, part military strategist and leader) before forgetting God and restarting the cycle all over again.

Jael lived during the time of Deborah—the only female judge recorded in Scriptures—a woman so formidable that even Barak, her associate and military commander, deferred to her wisdom.

Guided by God, Deborah led Israel to battle against Sisera, a Canaanite commander serving a king who oppressed Israel. As his army fell, Sisera fled like a coward. He ended up seeking refuge in the tent of Jael, whose husband—though he was an ally of the Israelites—was on neutral terms with the Canaanite king. Sisera welcomed him, gave him milk, let him rest—then, while he slept, she drove a tent peg through his skull.

Here’s my handy mnemonic for remembering Jael’s name: don’t impale people in the face unless you want to go to JAEL.

Except, Jael didn’t go to jail. Instead, she was praised in Deborah’s victory song on language that vaguely foreshadows the Magnificat of Mary in the New Testament:

“Most blessed among women is Jael,

the wife of Heber the Kenite,

May she be blessed above all women who live in tents.” (Judges 5:24)

Maybe Deborah just didn’t know about the vicious impaling/ But no—the song gives a play-by-play of the execution (in case you ever need to know how to kill someone stronger than you), followed by a gut-punch scene of Sisera’s mother waiting for her son to return home.

Then the finale:

“Lord, may all your enemies die like Sisera!” (v. 31)

Now that we’ve got the gist of what happened, back to my youth pastor’s tip: what’s the practical application here? Besides, you know, proper technique for killing someone much stronger than you (step one: warm milk).

Honestly? I have no idea. Some parts of the Bible are easy to know what to do with—they fit nicely into the tidy fabric of Sunday School morality. Others are more complicated, but eventually—with a little pushing and pulling—can be crammed into the grid.

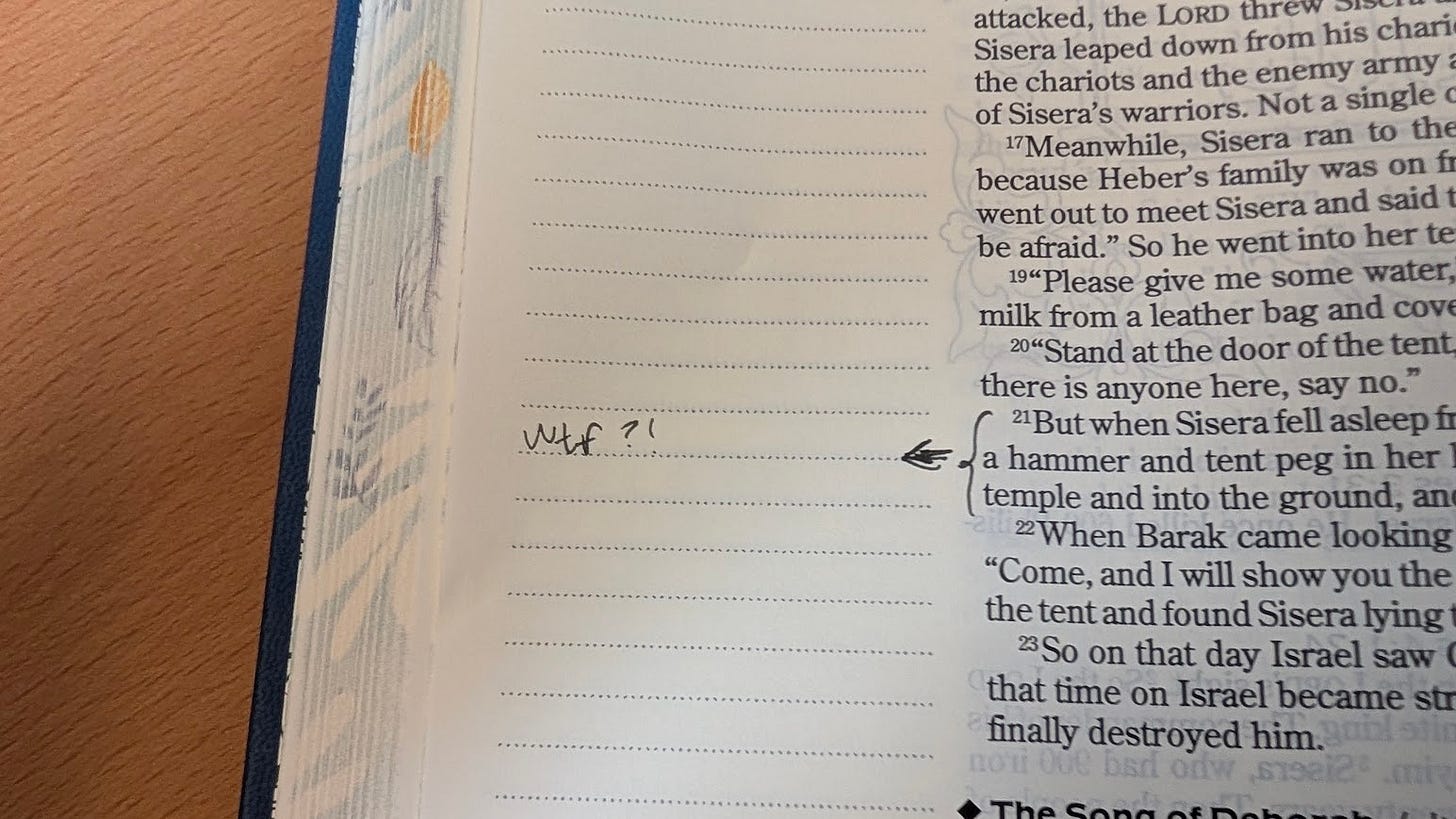

Still others parts of the Bible never come close to fitting. They are too bloody or jagged or… stake-like… for our tidy categories. This is usually when I write things like “WTF?!” in the margins of my Bible. Let that final letter stand for whatever you want it to—fudge, fig, any delicacy starting with F will do. For me the acronym is shorthand for conglomerated exasperation, confusion, and disgust. This is how I wrestle—with the Bible, God, myself, reality. It’s usually aimed at God. Everyone knows the Israelites were messed up, but the Lord of Hosts should know better.

Needless to say, there are a few marginal “WTF?!s” beside the story of Jael. I’m not sure what’s more troubling: that she kills someone while they slept, or that she is revered as a heroine by the same people God had led into battle. Is this the same God whose Son, some fifteen-hundred years later, would tell us to “Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, so that you may be children of your Father in heaven” (Mt 5:44, 45 NRVUE).

Maybe (probably) in that time—before Christ, before human rights, before the Geneva Convention clauses on just treatment of war criminals—the Jael episode landed differently. Maybe people needed military victory to believe God was real and active. Maybe that was the only way they could imagine Him loving them. Maybe.

But what I see, over and over in Israel’s history, is that even the best victories feel a little like failures. We are told, after Deborah’s song, that there was peace in the land for forty years, but at what cost? And to what end? Any peace Israel managed to enact was forged in blood. And it was always flimsy and temporary—it was only a matter of time before they would forget God and fall under the oppression of yet another foreign king. And especially during the time of the Judges, their relationship with God was less a living, thriving connection and more a series of blood-borne transactions. Sacrifices, laws, and a few years’ faithfulness in exchange for a decisive military triumph. Even their songs of praise are full of war and vengeance.

And what of God? What if these accounts are handed down to us not so much as a divinely sanctioned bellicosity, but rather to show us—over the longue durée of the salvific story—how far God desires to bring Israel. From skull-stabbing “heroines” to martyrs who forgive their persecutors—and beyond. And to show us that God deigned to dwell with Israel, even then, as sad and disgusting and vicious as the circumstances sometimes proved.

I’m struggling to say what I mean, because there are many times when God—or at least God-as-communicated-by-Ancient-Jewish-Cultural-Norms—seems complicit in or even responsible for these challenging stories.

What I do know is that this is life after the Fall—this is life in Israel, and this is life today. Even the best moments of humanity’s relationship with God after the Fall are pretty pitiful—not because of God, but because of us. How many times have I looked at a news headline and felt the same revulsion as I did reading Jael’s story? How many times have we mistaken pride and prowess as prosperity? How many times have we forced a kind of flimsy peace through needless violence? How many times have we forgotten God?

How many times have I looked at a news headline and felt the same revulsion as I did reading Jael’s story? How many times have we mistaken pride and prowess as prosperity? How many times have we forced a kind of flimsy peace through needless violence? How many times have we forgotten God?

Maybe the takeaway is that there is no neat takeaway. Maybe sometimes, instead of forcing every passage into a tidy life lesson, we need to sit with the discomfort, the ick factors, the stench of coagulated milk and blood in some desert tent. Maybe the point is not to apply these stories, but to meet God in the difficult, tenuous mystery of His dealings with humanity—especially when humanity is at its most vicious.

Hey there! Please check out the »Community Guidelines of this blog before commenting. Thanks for helping me continue to make this a safe, supportive, and gracious community.

"And what of God? What if these accounts are handed down to us not so much as a divinely sanctioned bellicosity, but rather to show us—over the longue durée of the salvific story—how far God desires to bring Israel. From skull-stabbing “heroines” to martyrs who forgive their persecutors—and beyond. And to show us that God deigned to dwell with Israel, even then, as sad and disgusting and vicious as the circumstances sometimes proved."

I like this. I've heard it said that we have be careful in discerning what is merely descriptive (simply recording something that happened) vs. what is prescriptive (setting out some kind of divine decree or rule).

While Deborah's song of praise is an affirmation of Jael's actions, some of the most "WTF" moments in the Bible are much more ambiguous, in that the Bible offers neither clear condemnation nor approval of them. Take for example the aftermath of the rape of Dinah. Her brothers tell Shechem that they'll give him Dinah if all the males in the town are circumcised. Then when they're recovering from their circumcisions, Simon and Levi come into town, slaughter all the men, plunder the city, and take the women and children captive. Jacob is angry at them—but for making trouble with the locals, not because he sees their actions as wrong. Simon and Levi respond "Should he treat our sister like a prostitute?” (Genesis 34:31) And that's how the story ends—with their question unanswered. WTF indeed.