Resurrection and the Wounds that Remain

The wounds of Christ, St. Macrina, and what it means to carry hope in a scarred body

IT WAS DEEP IN THE FOURTH CENTURY when St. Gregory of Nyssa stood over the reposed body of his beloved sister, St. Macrina. At his side, the nun Vestiana leaned with hunched shoulders over the body and began to lift the cloak covering Macrina’s chest.

Gregory recoiled—modesty, even in death, was sacred.

But Vestiana stopped him.

“Do not let this miracle pass by unnoticed,” she said, bringing a candle to illumine Macrina’s skin.

Her gesture drew Gregory’s eyes to a place that had always remained hidden: a scar, thin and red, marked one of Macrina’s breasts.

“Why should that surprise me?” Gregory asked with a shrug.

“Because,” replied Vestiana. “Because it is what remains. A reminder of God’s powerful help.”

Then she told him the story: years earlier, Macrina had nearly died from a great tumour that afflicted her body in that very place. No doctor was summoned—Macrina, in her modesty, refused to expose her body for examination. Her mother, St. Emmelia, had wept, begging her to seek help. Still Macrina refused. Instead, she asked her mother to pray and trace the sign of the cross on her body. The tumour soon vanished.

But the scar never went away.

“It took the place of that terrible sore," Vestiana whispered, "and stayed to the end—a reminder of God’s mercy, I imagine, a memorial of His divine visitation, a reason for perpetual thanksgiving… Do not let this miracle pass by unnoticed.”

Do not let this miracle pass by unnoticed.

In a few short days, we will celebrate the Holy Resurrection. In the brilliant light of Pasha, the shadows of Lent and Holy Week will recede. The sorrow, the fasting, the ache, the logistical chaos—they will soon be forgotten until next year.

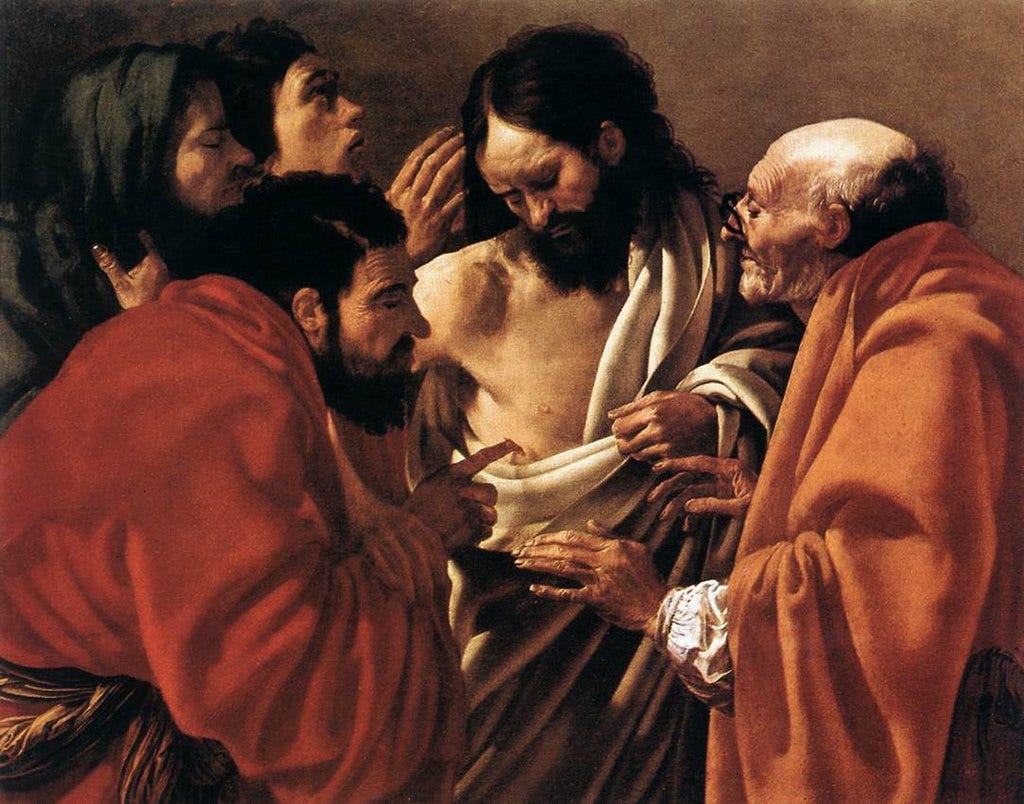

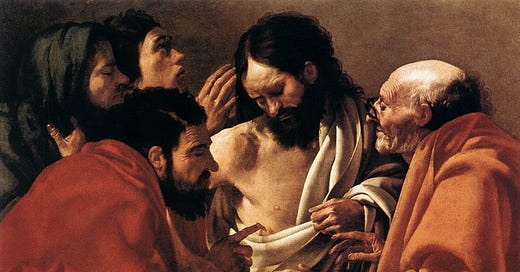

But Christ does not forget what He endured, and neither does His body. The Gospel accounts tell us that after the Resurrection, Christ still bore evidence of His suffering in the form of imprints and scars. Instead of vanishing or regenerating like the rest of His risen form, His scars remained as proof of His love.

The shape and location of Christ’s wounds were what allowed some of His followers to even recognize Him, let alone have faith in His true Resurrection. Perhaps some of our scars, too, are part of what have shaped us, made us recognizable as the unique, Mysterious, image-bearing children of God each of us are and are becoming.

Theologian Shelly Rambo speaks of this as the “ongoingness” of trauma, how it doesn’t disappear with time, but lingers, continuing to shape our lives in body and spirit.

The Resurrection does not erase suffering. Instead, it carries it forward, wrapping it in life and light and transforming it with the fullness of meaning.

“[R]esurrecting is not so much about life overcoming death as it is about life resurrecting amid the ongoingness of death. The return of Jesus marks a distinct territory for thinking about life as marked by wounds and yet recreated through them.”

—Shelly Rambo, Resurrecting Wounds: Living in the Afterlife of Trauma (p. 7)

Here is one of the deepest paradoxes of our faith: healing—even the miraculous kind—does not mean erasure. Sometimes, it means the build up of scar tissue. Sometimes it means the wound remains tender; covered, but never fully forgotten.

Not only do the scars that remain on Christ’s body provide visible witness to the embodied reality of His death and resurrection, they also pave the way for our scars to bear and convey God’s visitation in our own lives. In our own traumas.

We all have wounds. We all carry scars—some visible, some we conceal, others we bury so deep we may not even be aware. Some of those scars may be the result of our own mistakes or shortsightedness. Others the imprint of sin, injustice, or evil of other humans on our body. Still others may be no one’s fault—like Macrina, they may result from the sickness and brokenness that pervade every molecule of life on this side of Eden.

Whatever reason for our scars, like those of Macrina or Christ himself, they bear the potential to become witnesses—not just to what we’ve survived, but to how God has mystically shown up in the midst of it. To the astounding fact that grace didn’t skip over the painful or scandalous parts, but met us there—in the flesh. In the softest parts of who we are.

So yes, let us celebrate. Let us sing, rejoice, feast the night away (or have a fun snack and go to bed, which is my usual post-Paschal vigil game plan).

But let us also remember…

Do not let this miracle pass by unnoticed.

Wishing you all the best for what remains of your Holy Week, and a blessed Pascha.

In Christ,

Nicole

Sources used in this article:

St. Gregory of Nyssa, Life of Macrina, Tertullian.org

Shelly Rambo, Resurrecting Wounds: Living in the Afterlife of Trauma (Waco: Baylor University Press, 2017), esp pp. 1-16.

“I walk to God on a scar. The hurt shows me the way” the line I open my poetry collection with. Thank you for this post.

Thank you for this beautiful reminder. May you finish strong! A blessed and wondrous Resurrection to you and yours Nicole! ☦️