So much of today’s online discourse—including in Internet Orthodoxy—reduces femininity to a narrow, dubiously “traditional” script: stay sweet, stay married, stay home.

The so-called “trad wife” aesthetic—often styled in soft florals and sourdough starters—may look like wholesome, Christ-centered femininity at first glance. But more often, it’s secular patriarchy in brand-sponsored clothing, romanticizing a past that never quite existed while minimizing the harm rigid gender roles can cause.

True holiness has never been this tidy, or this demure.

In today’s post—part of my »“Saint Roundups” series highlighting saints who challenge conventional assumptions—I’m sharing three ancient Christian women saints whose examples defy the trad wife aesthetic in all the best ways. These women remind us that sanctity isn’t about domestic perfection or passive obedience, but about turning with boldness toward Christ, no matter the cost.

To be clear: I’m not criticizing women who freely choose a stay-at-home life, are treated with respect and dignity by their partners, and who find joy in domestic labour. (Indeed, as I write this, I’ve got a loaf of sourdough rising on the counter… admittedly I did not mill my own flour.)

What I am pushing back on is the idea that Christian woman- (or man-)hood must look one particular way. And that we are allowed to judge others or ourselves by whether our lives match such narrow, man-made ideals. The trad wife trend flattens the fullness of femininity into a single, prescriptive mould—one often designed to please men and algorithms, not God.

What I am pushing back on is the idea that Christian woman- (or man-)hood must look one particular way. And that we are allowed to judge others or ourselves by whether our lives match such narrow, man-made ideals. The trad wife trend flattens the fullness of femininity into a single, prescriptive mould—one often designed to please men and algorithms, not God.

And for those unfamiliar: the “trad wife” (short for “traditional wife”) phenomenon is a social media-driven aesthetic and ideology that idealizes hyper-traditional gender roles—women staying home, submitting to their husbands, and rejecting careers or professional autonomy in favor of domestic life. In some versions of trad life, the woman even votes according to her husband’s political preferences. Often cloaked in Christian language, this phenomenon promotes an ideal that can quietly reinforce harmful power dynamics within homes and communities, and isolate women under the guise of holiness.1

But enough about that. Let’s get to know three saints whose lives help us tell a very different story about what it means to be a human being seeking Christ…

1. St. Anastasia of Rome: Deliverer of Poisons

Commemorated: Dec 22

St. Anastasia of Rome was no homemaker baking bread in peace (no offense to those who would like nothing more than to bake bread in peace, myself included).

Born to a pagan father and a secretly Christian mother, St. Anastasia was educated in the faith by her teacher Chrysogonos. After her mother’s death, her father married her off to a pagan man named Publius. Anastasia resisted consummating the marriage by feigning illness and secretly dedicated herself to helping imprisoned Christians, disguised in beggar’s clothing. When Publius found out, he beat her and confined her to the house. 👀🚩

It was only after Publius’s sudden death at sea—foretold by her teacher Chrysogonos—that she was set free to live out the calling God had placed on her heart. She gave away her possessions and spent the rest of her life traveling from city to city, healing the wounded, comforting prisoners, and remaining unshaken by threats, torture, or even starvation.

Through her prayers and intercessions, St. Anastasia healed many who had been harmed by potions, poisons, spells, and other deadly substances, earning her the title Deliverer from Poisons (ἡ Φαρμακολύτρια). Her compassion and miraculous deeds became widely known, eventually drawing the attention of authorities during the fierce persecutions under Emperor Diocletian. Arrested for her unwavering faith, she endured severe torture and countless torments before ultimately being martyred by fire around the year 304.

3 things I love about St. Anastasia:

Holiness is not found in staying quietly married at all costs. Today’s “trad wife” culture often frames a woman’s life around her husband’s authority and comforts, glamorizing domesticity while downplaying the harm such isolation and enmeshment can foster. Anastasia offers a striking alternative. Her life doesn’t romanticize the torment she endured in marriage, nor does it sanctify the suffering caused by a destructive marriage. Instead, she seeks deliverance—and receives it. Far from being chastised for her unwillingness to submit to her abusive husband’s desires, she’s eventually freed to live a single life with strength, intellect, and deep compassion.

Sexual coercion is not white-washed out of her story. That sexual violence features in her story is unique (though not an isolated instance, see also St. Teneu of Scotland and St. Markella) in the lives of saints. Hers is a story we can look to as we seek to dismantle stigma and shame around intimate partner violence, particularly in marital contexts (see also the life of St. Thomais of Lesbos). Even in modernity, it’s taken generations to acknowledge that abuse and sexual violence can happen within a marriage—that being someone’s wife doesn’t mean forfeiting your safety or consent. More recently, the rise of purity culture and the “trad” ethos tends to prioritize male entitlement over a woman’s bodily autonomy, often under the guise of falsely spiritualized language or gender norms. What’s striking in Anastasia’s life is that God does not shame her for resisting her husband’s demands or failing in some kind of wifely duty. Instead, He makes a way for her to be free and safe.

Her womanhood is not defined by fertility, homemaking, or submission to men, but rather by her unwavering fidelity to Christ and her relentless care for the suffering. Through her faithful yet unconventional example, many have found healing, deliverance, and hope.

2. St. Anna (Susanna) of Leukadio: Dude gets what’s coming to him

Commemorated: July 23

Born in Constantinople in 840 during the reign of the iconoclast Emperor Theophilos, St. Anna came from a wealthy, influential, and pious family. Raised in the “discipline and admonition of the Lord” (Eph 6:4), Anna was known not only for her beauty but also for her deep spiritual devotion from a young age. When her parents died, she inherited a substantial estate, which she shared with the poor.

As a young woman, her beauty caught the eye of a powerful Arab man living in the city, who sought her hand in marriage. He even obtained imperial approval to marry her (how romantic). But Anna wasn’t interested, and refused the proposal. Unable to take no for an answer, the man harassed and threatened Anna, demanding to marry her whether she agreed or not. 👀🚩

Desperate and tearful, Anna turned to God for deliverance. According to her life, God intervened and the man died shortly thereafter.

Anna went on to live a long life of prayer, fasting, and an absence of any further tyrannical suitors. When afflicted by a sickness at the end of her life, she quietly delivered her soul to God.

3 Things I Love about St. Anna of Leukadio

The guy gets what’s coming to him for once. So many virgin martyrs in Christian history were killed simply for saying no to a man. It's painful to read how often male entitlement turns deadly. That’s why I find St. Anna’s story important: when an aggressive suitor refused to take no for an answer—even with an emperor’s blessing—God stepped in. Anna prayed for deliverance, and the man dropped dead. Like the story of St. Anastasia of Rome, above, St. Anna’s life reminds me that God doesn't glorify suffering for its own sake. Sometimes, God’s love looks like removing us from harm.

She’s not a martyr. I love a good martyr story, but I find them less relatable since I personally do not live in a time when I’m literally choosing between Christ or having my head chopped off. Anna lived a long, peaceful life of prayer, generosity, and devotion. Not every saint dies a bloody or dramatic death. Some live simply and finish quietly, which can be just as holy.

She wasn’t especially noteworthy. This particular St. Anna is not a household name among the saints. Her life wasn’t flashy (love letters/imperial decrees from her Romeo aside), and I couldn’t even find a icon of her to include in this post (lots of other St. Annas and Susannas out there, but none that seemed to be her). But that’s the beauty of it. Anna took what she had—a godly upbringing, inherited wealth, a deranged suitor—and offered it back to God with a sincere heart. Following her death, when she was buried with her parents, her body was found incorrupt and miracles began to occur. She may have lived in relative obscurity, but not to God. And that’s enough.

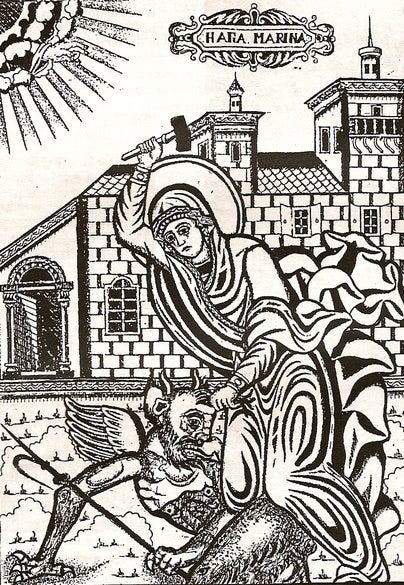

3. St. Margaret of Antioch: “Don’t make me get the hammer, Satan.”

Commemorated: July 17

Some saints’ lives read like a movie. Others like an FRP (fantasy role-playing) game—I think that’s where St. Margaret (or Marina) of Antioch lands. Her life is truly a saga, with too many fantastical elements and scenes to cover in this post, but you can read more about her »here, »here, or »here.

Born in the third century to a pagan priest, she rejected the expectations of her time (and family) by converting to Christianity at age twelve and vowing never to marry. When Olymbrios, the imperial governor in her region, asked Margaret to become his wife and renounce Christ, she refused. He tried unsuccessfully to woo her with power, wealth, and eventually brute force. 👀🚩

“Olymbrios offered her his hand and heart publicly, in the center of the city, from the prefect's podium, but Saint Margaret remained unwavering in her refusal.”2

Furious that Margaret could turn down such a man as handsome and powerful as himself, Olymbrios punished Margaret with imprisonment, public torture, and increasingly sadistic humiliations.

Amid this brutality, St. Margaret is said to have performed several miracles—including defeating Satan not once, but three times. These physical battles with Satan set her story apart from most other martyr saints, both female and male. My favourite story is when Satan appeared in St. Margaret’s prison chamber in the form of a dragon and swallowed her whole, she made the sign of the cross inside his belly and split the beast apart. (Did he not have any Tums in his »loculus? 🤔)

When Margaret was martyred in c. 304, 15,000 others were beheaded alongside her. Within a very short time after her repose, Margaret had become a powerful intercessor especially for those suffering misfortunes and troubles, and for victims of unrighteous judgment and lawless sentences.

“The Holy Great Martyr Margaret, who defeated the devil during her lifetime, protects us against the Enemy's slanders and defamations, she intercedes for those who are overwhelmed by the spirits of malice, the possessed and mentally ill, as well as for those who are on their deathbed, driving the demons away from them.”3

Three things I love about St. Margaret:

She may or may not have actually lived—and yet she was one of the most famous and influential saints of the medieval period. As someone prone to a bit of artistic hyperbole myself, I have a soft spot for saints whose stories stretch the bounds of believability. St. Margaret reminds me that while God loves truth and we should seek accuracy, He’s not above working through the wild edges of human storytelling and holy imagination. We don’t know whether St. Margaret actually lived, or how much of her story has been embroidered with time, but we do know many have been healed or found solace through her story.

Girl knew how to use a hammer. In some accounts, Satan appeared to St. Margaret in human form to defeat her. She immediately grabbed a hammer, seized him by the horns, and beat him down, shouting, “Depart from me, O lawless one!” In many artistic depictions, St. Margaret is featured with a hammer. I feel like she would have known her way around a Home Depot.

We hear her words—not just words about her—in many of Lives written about her (and even in some of the modern Orthodox Synaxarion entries for her). Were they her real, historical words (if she even existed—see point 1 above)? Likely not. But attributing spoken words to women saints reminds us that women, too, were created with voice and agency. My favorite example of St. Margaret’s words comes from a (non-Orthodox) 15th-century English account in which Margaret is interrogating Satan before shoving him into an abyss. He blathers on, listing all the holy people he’s tempted and basically mansplaining demonic powers to her. Eventually she decides she doesn’t have time for Satan’s endless monologue and cuts him off: “Flee hence, thou wretched fiend!” Not today, Satan!

What examples (saints, mentors, stories) have helped you expand your vision of what faithful femininity (or just humanity) can look like? Share in the comments below!

Hey there! Please check out the »Community Guidelines of this blog before commenting. Thanks for helping me continue to make this a safe, supportive, and gracious community.

This post has been lightly copy edited by Chat GPT.

Further reading on the dangers of the trad-wife phenomenon from a variety of Christian perspectives: Cait West, “I Survived Christian Patriarchy—the Tradwife Trend Is Hauntingly Familiar,” Newsweek (May 6, 2024); Sheila Wray Gregoire, “Why My Heart Breaks for Tradwife Influencers,” BareMarriage.com (January 24, 2024); Erin Ford, “How the tradwife social media trend is anti-gospel” (May 5, 2024); Rebekah R. S. Clapp, “The #tradwife Movement and Christian Womanhood,” Firebrandmag.com (February 25, 2025).

Oca.org. “Great Martyr Margaret (Margaret) of Antioch,” July 17, 2025. https://www.oca.org/saints/lives/2014/07/17/102042-great-martyr-Margaret-margaret-of-antioch.

Ibid.

St Catherine was a highly educated woman who overcame the best scholars in Alexandria, and also refused any husband but Christ. Her prayers helped bring me to Orthodoxy!

St. Macrina the younger, Church mother who taught the Cappadocian fathers their theology.