What Role Did Women Really Play in the Early Church?

Telling Her Story in the Christian East

In this article:

What role did women play in the early Church? Tell Her Story by Nijay Gupta offers some well-researched, historically grounded thoughts.

Why is this book relevant to Eastern Christians? Though writing primarily for Protestants, Gupta’s work affirms what Eastern hymns, icons, and liturgical traditions have long proclaimed—now with fresh historical insight and new questions.

Why does this matter today? In an age of cultural distortions about gender, Tell Her Story helps reclaim a fuller, truer vision of men and women as co-laborers in Christ.

Have you ever wondered what it was like to be a woman in the earliest, most tumultuous days of the church? Or wrestled with some of St. Paul’s words about women, unsure how to reconcile them with the gospel’s radical and gracious vision for humanity? Have you ever noticed how Christ entrusted women as the first apostles of His resurrection—then wondered why we basically never hear from them again?

These are questions many of us have carried, sometimes quietly, sometimes with a sense of confusion or uneasiness. Even those who, like myself, respect and uphold traditional teachings that reserve sacramental ministry for men still find ourselves asking: does faithfulness to this teaching require downplaying or erasing the vital roles women have played since the earliest eras of Church history? Moreover: does it require erasing ourselves, as women followers of Christ, today?

Does faithfulness to tradition require downplaying or erasing the vital roles women have played since the earliest eras of Church history? Moreover: does it require erasing ourselves, as women followers of Christ, today?

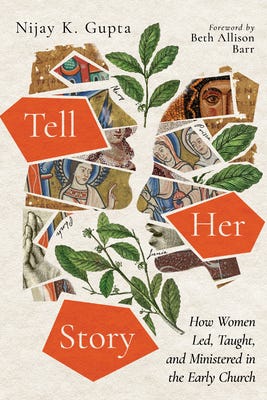

Recently I was grateful to read Professor of New Testament ‘s Tell Her Story: How Women Led, Taught, and Ministered in the Early Church (IVP Academic, 2023). This is not another modern agenda imposed onto Scripture—it’s a careful, scholarly excavation of what the New Testament actually tells us about the women who shaped the early church.

By examining New Testament texts alongside contemporary historical sources, Gupta sheds light on the active and complex—even ministerial—roles women played during the life of Christ through the apostolic era. While numerous books exist that focus on individual prominent women of this period—like Lydia, Phoebe, Mary Magdalene, etc.—Tell Her Story uniquely brings them together, with the men they worked alongside, exploring their lives and contributions in rich conversation with cultural and textual norms of the time. The result is a nuanced, vivid, well-researched account that is as edifying and surprising as it is historically grounded.

Why this book matters for Eastern Christians

Although Gupta seems to be writing primarily for fellow Protestants, I believe Tell Her Story, and books like it, are important for those of us living out our faith in Eastern Christian churches (Eastern and Oriental Orthodox, Eastern rite Catholic, etc.). Why? Because, perhaps more than any other Christian tradition, our worship and theology still bear a living connection to many of the women and insights Gupta examines. ETA: We can (and should) celebrate when authors of other Christian backgrounds discover and give voice to the inheritance of our shared Christian past, because it reminds us tradition is not our human possession—it is a gift from God to all of us who seek to follow Christ.

A professor at a private Protestant seminary, Gupta takes pains to unpack certain historical truths that, for Eastern Christians, are already deeply familiar—they still feature heavily in our hymnography, iconography, and liturgical life. For example, he highlights how Mary Magdalene’s honorific (“Apostle to the Apostles”) was one the early Church used to recognize the authority of her witness. For Orthodox Christians, this isn’t just a historical footnote—it’s a reality we proclaim (repeatedly) every paschal season, woven into the fabric of our liturgical tradition. Or take another example: the often-overlooked verse in Acts of the Apostles that places Mary, the Mother of Jesus, in the upper room at Pentecost (vv. 1:13, 14). We may not recall the verse directly, but our understanding of Pentecost, shaped through the icons and hymns that constantly surrounded us, actively and frequently reminds us that she was there. Finally, we also already honour many of the early women of the Church by name—Phoebe, Lydia, and Priscilla to name a few—not merely as distant historical characters but as familiar, active, interceding saints, celebrating their feasts, telling their stories, and taking their names at baptism.

And while Eastern Christian tradition upholds a male-only sacramental ministry, it does not do so from the rigid view that men are morally superior to or less fallible than women, but rather due to the Mystery of christology and our vision of sacramental reality. Indeed the faith handed down to us is one that rests on women and men working together for Christ, for the building up of the Church and the life of the world.

So in many ways, Gupta’s book won’t feel as revolutionary to Eastern Christian audiences as it might to many Evangelical or fundamentalist Protestant ones. Instead, it reads as a much-needed reminder of what we already know but may not always have words to articulate. It offers a more granular glimpse of how women and men ministered together in the early Church, grounding what we intuitively recognize in the lived historical realities of the apostolic era. It also gives us additional tools to navigate difficult passages of Scripture that speak about certain forms of women’s participation in ministry, especially those that have been misunderstood or misused as a way to silence women.1

Why this matters now

But beyond historical insight, Tell Her Story is important for another reason: it helps safeguard this beautiful, vital knowledge of men and women’s shared Christian past at a time when cultural and ideological warfare threatens to distort or erase it.

More than once in recent months, I’ve been told—both online and in person, in my own day-to-day Orthodox life—by certain Orthodox brothers in Christ that the Church does not ordain women because from the beginning they were created morally weaker than men, more prone to failure, or simply too emotional to handle leadership. I cross paths with more and more young women who are seriously considering celibacy—not because they genuinely feel called to monasticism, but because they doubt they will ever meet single men in the Church who aren’t, in some way, dismissive or contemptuous of women. Meanwhile, in certain corners of Internet Orthodoxy, ordained clergy can get away with building followings—even making money—off content that objectifies women, trivializes their spiritual gifts, or dismisses the God-given dignity of their personhood. And simply voicing an expectation for basic respect of women in public Christian circles is enough to get labeled a “feminist,” “feminazi,” “fembot,” “witch,” or worse.

This is the cultural moment we are living in. And it is not an easy one.

Such attitudes damage not only women but also men, and ultimately the whole way we relate to one another as brothers and sisters in Christ. They distort the gospel vision of men and women working together for the sake of the Kingdom.

And this is why Tell Her Story matters. Although I didn’t agree with every jot and tittle in Gupta’s account,2 I generally found it to be a useful corrective on both a personal and broader level. A thoughtfully crafted resource, it reminds us of our true inheritance as women and men, and as a Church. It calls us back to a history that is not about competition or erasure but about cooperation, human complexity, witness, and faithfulness. It also helps us more keenly recognize the ways secular, man-made patriarchy—not authentic Christian tradition—robs the Church of a fuller vision of men and women co-labourers in the vast vineyard of ministry and life in Christ. In doing so, it gives us something we can reclaim, return to, and build on.

This isn’t about rewriting Church history, it’s about remembering it rightly.

Hey there! Please check out the »Community Guidelines of this blog before commenting. Thanks for helping me continue to make this a safe, supportive, and gracious community.

This post has been lightly copy edited by Chat GPT.

E.g. in I Timothy 2:8-15—often seen as Paul’s harshest critique of women’s authority to “teach” in the Church—Gupta unpacks the linguistic, cultural, and historical context to argue that Paul likely wasn’t intending to issue a universal ban. Instead, he was likely addressing a specific situation in Ephesus where certain women were spreading false teachings and usurping authority in an abusive or toxic manner. This interpretation also makes sense given Paul’s own ministry—he openly relied on female teachers like Phoebe and Priscilla, and permitted women to prophesy (a role that, in the early church, carried significant, if not greater, teaching authority).

Here are some things I struggled with in Tell Her Story. I place them as a footnote because, to me, they were not major substantive concerns, and very much represent my own wrestling with some of the issues raised in the book.

1) I’m still not sold on the interpretation that the “prohibition passages” are only situational, in part due to baggage from my own legalistic past, and in part due to the fact I’m just not convinced. However, Gupta’s patient, transparent, and erudite analysis of passages like 1 Timothy 2 is probably the most helpful I’ve read. It still didn’t convince me, but his exploration of the textual, historical, and linguistic context of these verses helps me continue to appreciate that they are more complex than modern gender debates suggest. At the very least, I’m willing to accept that these verses in and of themselves can’t be used as simplistic proof texts to settle the debates on women’s participation in the church.

2) Gupta emphasizes the fluidity of early church leadership roles, often avoiding standard translations like "bishop" or "deacon" to highlight their interchangeable nature in the apostolic era. However, by the late first century, roles like episcopos were already becoming more defined, as is evident in the writings of St. Ignatius. Gupta’s reluctance to use clear terms implies that it was modernity that reduced the fluidity of these terms/roles, when really the interchangeability he’s talking about was more short-lived than he seemed to imply. For the record, I actually appreciated his point about referring to presbyters and deacons as “ministry providers,” I just think using that term instead of more standard translations was at times unclear and at other times slightly misleading.

Most Holy Theotokos save us!🪽🌐

Happy Feast of the Annunciation 🔥

Happy Feast of the Annunciation!

I'm sorry to hear you met with ignorance from some Orthodox brethren.

Mother Teresa once said (and I'm paraphrasing) that if priesthood were a matter of worthiness or morality, the Theotokos would've been made a priest.